By Amin Kef (Ranger)

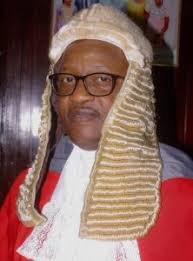

The Judiciary’s new Practice Direction on drug-related offences, issued by Chief Justice Komba Kamanda on 1 December 2025, continues to generate strong national debate, with several senior lawyers defending the directive as timely, lawful and essential for restoring order amid Sierra Leone’s worsening drug crisis. Leading this position is Joel Tejan Deen-Tarawally Esq., who argues that the directive has been widely misunderstood and that claims of constitutional violations are rooted in flawed interpretations of both the Criminal Procedure Act 2024 and the National Drugs Control Act 2008.

According to him, the directive in no way abolishes the presumption of innocence or bans bail, but simply reinforces the correct application of Section 76 of the CPA, which already guides courts on when bail may be withheld based on affidavits from the prosecution. He insists the Chief Justice acted fully within his authority to streamline procedures, promote consistency and reduce delays at a time when drug abuse, particularly Kush, has become a national emergency.

Support for the directive has also come from other senior legal voices. Austina Abioseh Thompson Esq., writing from Toronto, described the Chief Justice’s action as a bold continuation of a long-standing judicial tradition in Sierra Leone and elsewhere, where Practice Directions are used in emergency situations to ensure courts respond effectively to major threats to public safety. She noted that during Ebola, COVID-19 and the surge in sexual offences, similar directions were issued to guide Judges and Magistrates, and none were found to violate the law. She cautioned that resistance to the current directive appears driven by ill-motivated interests rather than a genuine concern for constitutional order, adding that no part of the directive prohibits bail absolutely. Instead, it merely restricts the power to grant bail to the High Court; an approach she likens to how murder, treason and life-sentence offences are handled.

In the United States, Dr. Abdul Rahman Bangura also defended the Judiciary, arguing that the directive provides necessary clarity for sentencing and ensures that drug manufacturers, traffickers and transporters face penalties commensurate with the gravity of their offences. He expressed concern that some critics may be attempting to shift public attention away from the severity of the drug epidemic for reasons he described as self-serving. For him, the directive neither undermines judicial independence nor contradicts existing laws, but instead helps close gaps that have long been exploited by those profiting from the drug trade.

However, despite strong backing from several legal practitioners, significant opposition has emerged from the Campaign for Human Rights and Development International (CHRDI) and the Lawyers’ Society of Sierra Leone, both of which argue that the directive is inconsistent with statutory provisions and risks weakening constitutional guarantees. CHRDI maintains that the National Drugs Control Act already grants Judges wide discretion to impose life sentences, minimum terms or suspended sentences depending on the facts before them. It argues that the new directive effectively limits those powers by introducing procedures not provided for in the Act, thereby elevating administrative instructions above the authority of Parliament. CHRDI further notes that Section 76 of the Criminal Procedure Act permits bail even in capital offences, provided certain conditions are met and warns that treating drug offences as non-bailable by default undermines due process, exacerbates prison congestion and could produce long-term economic and security challenges.

The Lawyers’ Society echoes those concerns, emphasizing that Practice Directions only carry legal force when supported by explicit statutory authority, which they say does not exist in the NDCA 2008. They argue that the Act assigns regulatory power to the Minister of Internal Affairs, not the Judiciary, and contend that the directive’s requirement that all drug cases be tried exclusively in the High Court contradicts provisions allowing summary trials for certain offences. According to the Society, treating all drug offences as High Court matters and tightening bail to the extent implied in the directive may amount to amending an Act of Parliament through administrative decision-making—an action they insist cannot stand under constitutional scrutiny. They caution that even in the fight against drugs, the presumption of innocence must remain intact, and judges must retain full discretion to determine bail and sentencing based on the individual circumstances of each case.

As both sides continue to press their positions, what emerges is a deeply felt national conversation on how Sierra Leone should confront its escalating drug crisis while preserving the rule of law. Supporters believe the Practice Direction strengthens the Judiciary’s capacity to respond decisively to a national emergency, while critics warn that no matter how dire the crisis, reforms must remain firmly within the bounds of constitutional and statutory authority. The debate is expected to continue as citizens, legal experts and policymakers weigh the delicate balance between urgent state action and the enduring principles of justice.